News

Warming seas push polar cod out of Iceland’s waters

A new long-term study from Iceland’s Marine and Freshwater Research Institute reveals that polar cod (Boreogadus saida) is steadily retreating from the waters around Iceland as ocean temperatures rise. The research draws on nearly 40 years of standardised trawl surveys and shows a clear pattern: as waters warm, polar cod retreat northward and into deeper, colder environments.

A keystone species under pressure

Polar cod plays a crucial role in Arctic food webs, funnelling energy from zooplankton to larger predators including seabirds and seals. Iceland sits at the very southern limit of their natural distribution and over the study period. The number of survey stations catching polar cod dropped sharply from 1985–2024 in spring and 1996–2024 in autumn. The remaining fish concentrated around Iceland’s colder northern and eastern waters.

Temperature measured by robust Starmon loggers

Since 1996, bottom temperatures during trawls have been recorded using Star-Oddi's Starmon TD temperature and depth loggers, which were attached directly to the trawl gear and recorded temperature every minute. Their data were used to validate and correct readings from the main sondes, providing a consistent, high-resolution temperature record over multiple decades.

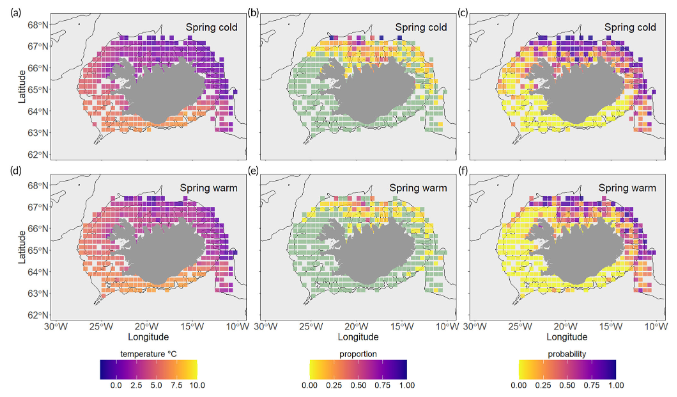

Fig. 7 from the article, with average temperature measurements.

Temperature as dominant driver

The analysis shows that temperature is the main factor determining polar cod presence. In the spring when adults approach their spawning season, occurrence plummeted at bottom temperatures above 2°C. None were found in waters warmer than 7-9°C. Using random forest models, the team showed that warm years consistently shrank the species’ suitable habitat, especially across Iceland’s northern shelf. Autumn patterns were less dramatic, likely because young cod are still descending from surface waters and haven’t yet settled into long-term habitat.

Continued withdrawal likely

The pattern seen around Iceland mirrors declines in the Bering and Barents Seas. With record heat in the North Atlantic during 2023–2024, the authors warn that the species may withdraw even further north if ocean warming continues.

The paper was recently published in the Journal of Fish Biology and can be found here